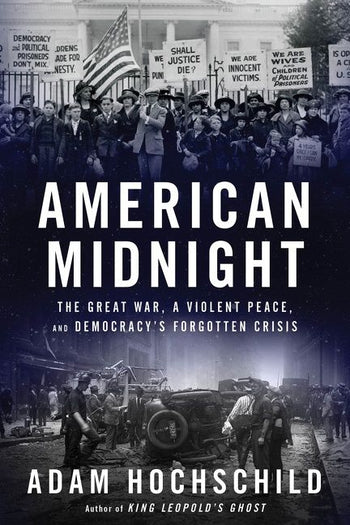

It’s been a while since I’ve posted, but that’s because I’ve been busy, and I’ve not had much to say. A few weeks ago I had a knee replaced, so I had to slow down for a while, which means I had some time to read. For mystery lovers, I recommend Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series. There are three books in the series, of which I’ve read the first two. The book I’m going to discuss today, though, is a history book, Adam Hochschild’s American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis.

For me, one comforting thing about being a student of American history is knowing just how much this country has endured and survived gives me hope we’ll get through whatever crisis we’re in at the moment. For example, when I hear someone say they’ll make America great again—or, as I recently heard from a past president, make America great and glorious again, I wonder what they have in mind. After all, it seems to me this country is pretty damn great—and even glorious—already. And I wonder exactly what changes these folks have in mind. And into this breach comes Adam Hochschild to remind me that we’ve been here before.

In 1917 Woodrow Wilson dragged us into World War I. As Hochschild points out, Wilson claimed he wanted to make the world safe for democracy. Unfortunately, the cost of making the world safe for democracy involved curtailing democracy significantly at home. Laws went into effect stifling freedom of speech. Any criticism of the war could land a person in jail. To enforce these draconian laws, the government effectively deputized civilian men (mostly) on the street, who, as you can imagine, became malevolent Barney Fifes—in one case bugging the barbershop of a German immigrant, who, with several of his customers, wound up in jail for their barbershop discussions. In a few cases, immigrants were lynched for… being immigrants.

Labor unions were targeted as well. Any time the country goes to war, a lot of money is going to be spent, and, oh my, Hochschild shows how defense contractors took advantage of the situation. But when labor decided it wanted a bigger piece of the pie, business and government turned against them. Violently.

Then, as now, immigration became an issue. Albert Johnson, who would later become notorious for the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act severely limiting immigration, is given a great deal of coverage in this book. Johnson, who attended schools in Atchison and Hiawatha, Kansas, would later move to the Pacific Northwest and become anti-labor and virulently anti-immigrant. Leonard Wood, who had gained some fame in America’s adventures in the Philippines, found himself stuck in Camp Funston at Fort Riley, Kansas rather than being allowed to fight overseas. He decided to make a run for the Republican nomination in 1920 opposing birthright citizenship. Almost a hundred years later, Ted Cruz, a child of immigrants who was born in Canada, would do the same.

Hochschild covers the early career of J. Edgar Hoover and the rise and fall of A. Mitchell Palmer, who would round up aliens and, if at all possible, deport them, preferably to the USSR. Palmer, who saw himself as just what the country needed, was grooming himself to be the Democratic candidate for president in 1920. He issued all sorts of warnings about imminent attacks to occur on May Day 1919. One thing about making predictions that specific is that, if nothing happens, you wind up looking like an idiot. After National Guards, deputized civilians, etc. had been called to protect the streets of America on the fateful day, nothing happened, and the “Fighting Quaker,” as Palmer had been called, wound up being laughed out of any political future and renamed the Quaking Fighter.

The book is 358 pages long, excluding notes,

acknowledgements, etc. Hochschild is an excellent writer, although a couple of

paragraphs about Wilson’s post-stroke condition appear out of place. As

Hochschild points out in his introduction, history books in general skip

immediately from the end of World War I to the Roaring Twenties. The eventful

years 1917-1921 deserve more coverage. This book is a great place to learn

about those dark years.

I take classes on a non-credit basis in history and literature at UMKC, and they do indeed talk about this in classes that cover the period 1917-1921, although they don't go into as much detail as Hochschild does.

ReplyDelete