A Review of Donald Yacavone’s Teaching

White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National

Identity

For many years I’ve been looking for

an excuse to write about my observations of race relations in the North and the

South, and now I have my excuse. But first, my observations.

I grew up in Oklahoma City when it

was segregated, first by law, and then for several years in spite of the 1954 Brown

v. Board of Education decision. My high school was segregated when I

graduated in 1966. The first very few Black students would integrate the school

in 1968. Other than the week each summer that I went to church camp, my first

encounter with Black people was when I went to college in 1966.

In 1970 a rumor went through my

parents’ neighborhood that a Black family would be moving in. One of their

neighbors was adamant that would not happen. My parents had built their house

in 1958 and had just paid off their mortgage. I should mention here my father

was not virulent, but he was a racist in the Southern sense. He did not like

Black people in general, but he did on occasion meet individual Black people he

liked or at least tolerated. I would compare him to Senator Bird in Harriet

Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who was a full-throated supporter of

the Fugitive Slave Act in the Ohio senate, but when faced with Eliza and her

son in his own kitchen, helps them escape further into the underground

railroad. I asked my father what he would do if a Black family moved in, and he

said, “No one who can afford to buy in this neighborhood is going to let their

property go down, and that’s all I’m interested in.” As it turned out, there

was no Black family moving in.

I’m going to skip ahead a few years

to a visit I made at Christmas in the 1980s. I was out with my sister, and we

passed a house in the neighborhood. My sister said, “Now don’t tell Daddy, but

a Black man lives there.” Another time I

was out with my brother, who said, “There’s a Black man who lives in that house,

but we don’t want Daddy to know.” Eventually, I was out with my father, who

said, “I think there’s a Black man who lives in that house. He’s a cop, and he

takes really good care of his yard.” And the neighborhood was integrated. It

soon became multicultural When we sold the house in 2013, we had competing

offers from a Hispanic family and a Vietnamese family.

I finished my degree in 1970. That

summer I took a graduate course taught by Dr. Jere Roberson at what is now the

University of Central Oklahoma. If memory serves, he had just moved to UCO from

Georgia. We were all steeped in the belief that the South was racist while the

North was not. Donald Yacavone and others describe this as the North’s sacred

“treasury of virtue” for having fought the Civil War and freed the slaves.

It would not be long before I saw

cracks in this sacred “treasury of virtue.” In 1971 I moved to Columbus, Ohio

for a job. I had only been there a few days when one of my coworkers told me

she and her husband were going to buy a home in a new development, but she’d

found out some Black people were also buying there, so she and hubby backed out

of the deal. I guess she thought I, being from Oklahoma and all that, would

understand. But I didn’t. I gradually learned that Columbus was quite

segregated. My real shock came when I moved to Long Island in 1974. I met the

most racist people on Long Island I have ever met. Bar none. We had one Black

secretary where I worked, and I don’t know how she did it. People were rude and

condescending.

One incident stands out in my

memory. A white family sold their house in Rosedale, Queens to a Black family

who moved from London in 1975. The white family’s former neighbors picketed

their new home in Westbury. And then, in January 1975, the Black family’s new

home in Queens was bombed. As the owner of that home said, “In England, you hear about this

happening in the South, but you just don't think it happens in New York City.”

So much for that sacred “treasury of virtue.”

Lest you think that was nearly fifty years ago and things are

surely different now, I’ll direct you to a 41-minute 2021 Newsday documentary

titled “Long Island Divided: How Real Estate Agents Treated Undercover Clients

on Long Island,” which resulted from a three-year investigation.

(https://www.google.com/search?q=newsday+unequal+treatment&oq=news&aqs=chrome.0.69i59j69i57j0i512j0i131i433i512j0i131i433j69i61j69i60l2.3574j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:2018caa4,vid:wqN-D3f49fE)

OK, so now the book. I read a review

of Teaching White Supremacy and didn’t know what to expect. I found the

cover, which, as you can see, is an 1873 print celebrating westward expansion,

railroads, the telegraph, overland mail delivery, and features a woman floating

in the air carrying a school book while holding one end of a telegraph line,

off-putting. Other than (possibly) the school book, what does any of this have

to do with teaching? Fortunately, I started reading the book anyway, and oh,

my. The more history I read the less I find I know.

If a high school student today is

taught about slavery and the Civil War at all, they’re taught the North was

against slavery and the South was not, which is far from the truth. For one

thing, the textile mills in New England, which employed people, including

children, in deplorable conditions which were often worse than slavery, relied

on cheap cotton, and cheap cotton depended on slavery. And that’s just one

example of how the North was just as reliant on slavery as the South. As

Yacavone points out, some of the earliest history textbooks, most of which were

published in the North, portrayed slavery in a favorable light, and almost

every one of them described slaves as having been lucky to have been “rescued”

from the wilds of Africa and brought to Our Christian Nation. Slaves were

almost universally portrayed as ignorant and of a species somewhat below that

of the white race. Even abolitionists bought into that, hating slavery but

having no use for the people who were slaves. Even Harriet Beecher Stowe sent

most of her escaped slaves off to Africa in the end. In a New York Review of

Books review of Kris Manjapra’s Black Ghost of Empire: The Long Death of

Slavery and the Failure of Emancipation Sean Wilentz points out white

abolitionist societies were not integrated. In short, at the end of the Civil

War, a fully integrated society does not seem to have been the goal of anyone.

And there were those who wanted to make damn sure it never happened.

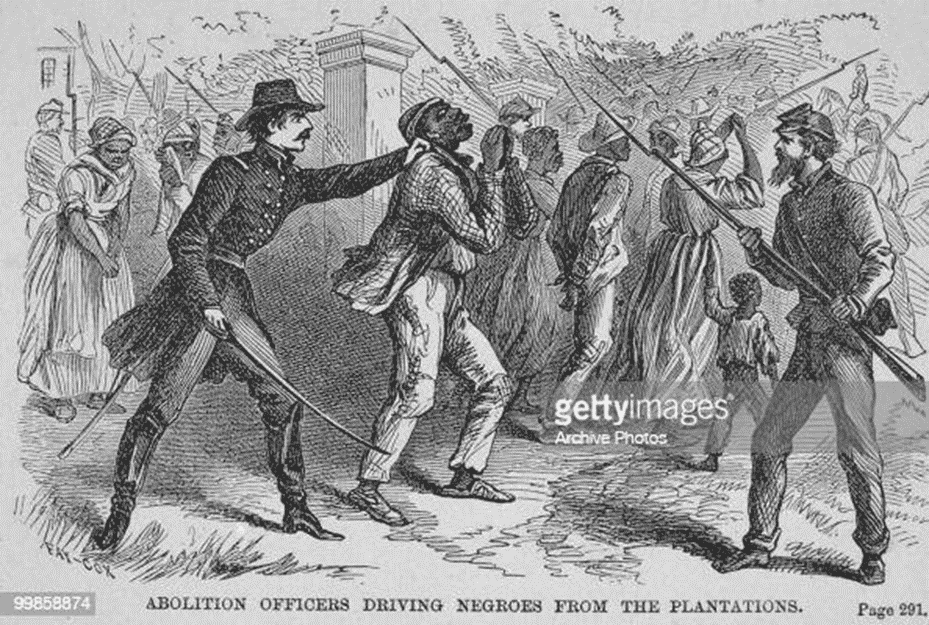

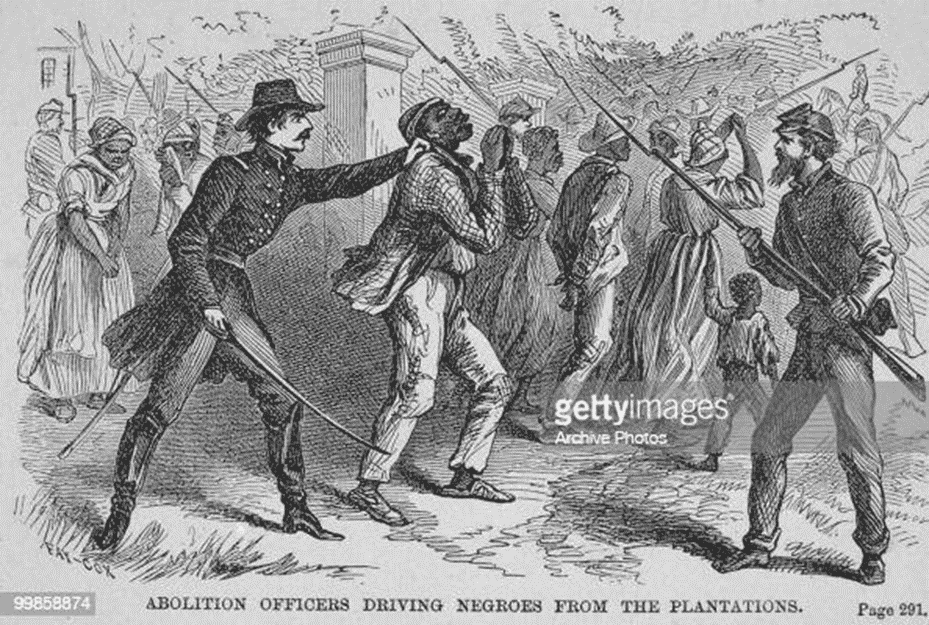

After

slavery ended, the goal of many writers of history was to emphasize how well

slavery had worked, with happy slaves, kind masters, and all that. One of the

ones Yacavone discusses is John H. Van Evrie (1814?-96), who wrote from the

1850s to 1879 and blamed the Civil War on northerners and abolitionists

cooperating with British agents in Canada. In one of the more amusing passages

in Van Evrie’s work, published under his partner’s name, Van Evrie wrote that

after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the North sent an “abolition

army” into the South to compel “negroes” to be free to do as they pleased, go

where they pleased, and be as lazy and useless as they pleased. Alas, it seems

the slave population remained entirely loyal to their masters and refused to

leave their plantations. The “invading army” found “the negroes” so devoted to

their white masters that Yankee soldiers had to tie them up and threaten to

“bayonet them” to force them out of their homes.

Yacavone takes us through several

cycles of teaching white supremacy including the emancipationist challenge,

1867-1883, roughly coinciding with Reconstruction, what he calls “causes lost

and found,” 1883-1919 in which he describes the ascendancy of the Dunning

School (which was still being taught when I was in high school and an

undergrad), “Eugenocide,” the 1920s in which the “science” of eugenics was

added to the white supremacist formula, the Lost Cause victorious, 1920-1964

during which Robert E. Lee morphed into a national hero meriting statues North

and South and it would have been blasphemy to say anything good about

Reconstruction, and finally renewing the challenge, which discusses the impact

of the new school of historians, who have actually gone back and reviewed

primary documents rather than merely building on the bad history written by

previous historians. I was exposed to some of the new thought in grad school at

The Ohio State University in the 1970s.

The book

mentions so many texts and writers it is hard to keep them straight. There are

many villains, but there are also heroes, among them Albert Bushnell Hart

(1854-1943), a Harvard historian who set aside his own prejudice to mentor some

of the country’s most influential Black scholars, including W.E.B. Du Bois.

I do have

a couple of minor nits to pick with Mr. Yacavone, both of which appear on page

278. The first is the wall that was constructed in Detroit in the 1930s to

secure FHA financing for a housing development was in the Eight-Mile area and

was a half mile long. It was not, as Yacavone writes, eight miles long. Second,

he says that from 1865 to 1934 the federal government distributed 246 million

acres of Western lands to 1.5 million white families. The land was available to

Black families as well. My grandparents homesteaded in Colorado, and one of

their neighbors was Black. As I said, these are minor, but this country’s

treatment of Blacks is bad enough. There’s no need to embellish!

As I was

finishing the book the thought occurred to me that perspectives on the Civil

War, slavery, and Reconstruction have gone through several iterations, and who

is to say they won’t revert back to Dunning or even Van Evrie? As if reading my

mind, Yacavone in his epilogue discuses the January 6, 2021 assault on the

Capitol and notes the many Confederate flags that showed up that day. He notes

the history wars, the fact that high school history, when it is taught at all,

is often taught by coaches who have no training in the subject. As a result a

majority of students with a diploma are ignorant of the basic facts of American

history and are at risk of being led to believe just about anything about our

past. I find that scary. How about you?

The book

is excellent. I get most of the books I read from the library, and there are

very few that I like well enough that I want to own for future reference. This

is one of those books.